An excerpt from Professor Mary Dixon-Woods’ 2018 Harveian Oration

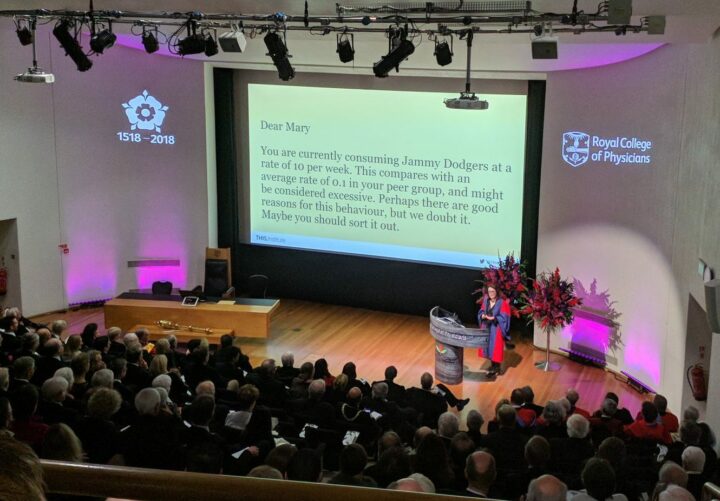

On 18 October 2018, THIS Institute director Professor Mary Dixon-Woods delivered the Harveian Oration at a gathering of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) in London.

The oration was established in 1656 by English physician William Harvey, the first person to describe accurately the circulation of blood in body. Each year, a leading doctor or scientist is selected to speak about important issues in their field.

In her presentation, Professor Dixon-Woods described challenges in quality and safety in healthcare, and proposed a way forward for improvement founded on evidence. An excerpt from that presentation follows.

The full video is available to watch on RCP London’s website.

You can read the full transcript in Clinical Medicine.

Both healthcare and research about healthcare have had a bad habit of admiring problems: describing them beautifully, but not actually solving them.

Bad things happen, or good things don’t happen, and too often the next action is to describe them again, whether through confidential inquiries, public inquiries, incident reporting, root cause analyses, clinical audits, patient and staff surveys, or any of the many systems for harvesting data about quality and safety across the NHS.

(…)

But the proportion of effort that goes into collecting data about problems and the proportion that goes into addressing the problems is often seriously imbalanced.

But the proportion of effort that goes into collecting data about problems and the proportion that goes into addressing the problems is often seriously imbalanced.

(…)

A relatively new field of practice devoted to the doing of improvement has now emerged. One of the most prominent of these (but far from the only) is distinctive set of practices known as quality improvement (QI), or sometimes as improvement science.

(…)

QI has been promoted as a way of addressing many of the pressing challenges faced by health systems, including its promise that, by reducing variability and improving process control, it will deliver better efficiency, value, consistency, and experience.

(…)

Some NHS organisations have embarked on ambitious QI programmes. Recent years have seen the emergence of a generation of QI practitioners – people whose roles include the doing of improvement as part of their jobs, and who have often had formal training in one or more improvement methods. Improvement academies are now springing up as interest in the “how to” of improvement grows. Professional regulators, including the GMC and the royal college, are now requiring that many professionals have some exposure to QI through their requirements for accreditation and qualification.

it is reasonable to ask: if QI is so good, why don’t all healthcare organisations do it?

Though many signals of increasing QI activity are evident, it is probably fair to say that uptake is still very uneven. In many ways this is a puzzle. Given the known defects in health systems, it is reasonable to ask: if QI is so good, why don’t all healthcare organisations do it? Why is it such a hard sell? And if thousands of professionals are now mandated to do QI or clinical audit, why are the benefits not more visible?

The reasons are multiple. It is hard to build awareness and capacity quickly. Not all organisations know about QI, and those that do have to balance many competing priorities with developing improvement capacity. There are many other explanations (not the least of which is) the weakness of the evidence-base supporting QI. It remains much too difficult to answer the question: does quality improvement improve quality?

It is, for example, surprisingly difficult to demonstrate the effectiveness of any specific QI approach, making it hard to give a clear answer to the chief executive who asks the very reasonable question of which she should adopt in her organisation. Cost data for QI is scarce, so return on investment for hard-pressed organisations with many competing priorities is difficult to establish.

Faced with this, it is perhaps not surprising to find scepticism and reluctance to invest in QI. It is obviously important for this, and for other reasons, that the field of practice benefits from a strong evidence-base that shows what works, what doesn’t, and why.

(…)

challenges that confront healthcare need to be solved at the level of entire systems, not organisation by organisation.

Many of the quality and safety challenges that confront healthcare need to be solved at the level of entire systems, not organisation by organisation. The royal colleges have an important role in putting the “national” back into the National Health Service by convening and coordinating the responses to challenges, ensuring that procedures and systems are designed with the right expertise, tested properly, implemented with professional leadership at the core, and remain open to innovation.

The royal colleges, with their unique and respected voice, can also take on important roles in political advocacy, not least by forming important alliances with patients and other stakeholders, and by advocating for action on problems where the responsibility lies outside healthcare itself – for example, in the ongoing failure to address issues of alarm fatigue, incompatible devices, or drug-naming and packaging practices.

Healthcare has many quality and safety challenges. A lot has been learned about how to address them; an awful lot still needs to happen. Much can be achieved, I propose, by ceasing to admire problems and put the effort into solving them in an evidence-based way.

Note that this excerpt has been edited to fit the format of this blog. Professor Dixon-Woods’ full presentation, entitled “Improving quality and safety in healthcare”, will be published shortly.

At the time of writing, the presentation is still available to watch on RCP London’s live stream – skip to 37:00 to watch Mary take the stage.