Brigden, T.V., Mitchell, C., Kuberska, K. et al. A Principle-Based Approach to Visual Identification Systems for Hospitalized People with Dementia. Bioethical Inquiry (2023).

A principle-based approach to visual identification systems for hospitalised people with dementia

Why it matters

Many hospitals in the UK use visual identifiers to help them improve the care of people affected by cognitive impairment. Visual identifiers include things like stickers, wristbands and badges that discreetly indicate that someone may be suffering from cognitive impairment and should prompt those involved in the person’s care to adapt their behaviour to suit the person’s needs. Although the use of these tools is recommended by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and they may have a positive impact, they can also pose risks to patients which have to be considered and mitigated against.

There are many visual identification systems for people with dementia or cognitive impairment, but so far, there hasn’t been any thorough consideration of the ethical or legal considerations that might arise when using them.

In this paper, we develop a framework for using identifiers for hospitalised people with dementia (and other forms of cognitive impairment) and suggest a set of principles to assess the benefits and the risks. We consider the implications of these principles for using visual identifiers along with the legal framework and policy landscape in the UK, and the potential trade-offs between them.

Our approach

This study is part of a wider research programme which examined ways that visual identification systems for people with dementia are designed and used. The overall objective of the programme was to better understand the use of visual identification for people with suspected or diagnosed dementia in hospital settings.

This phase of the study involved an analysis of ethical and legal issues, which then provided a framework used in later phases of the study. We conducted desk research to identify documents discussing the ethical and legal considerations that might arise in the course of using visual identifiers for hospitalised people with dementia. As there was little information available about visual identifiers themselves, we broadened the search to relevant literature on similar subjects.

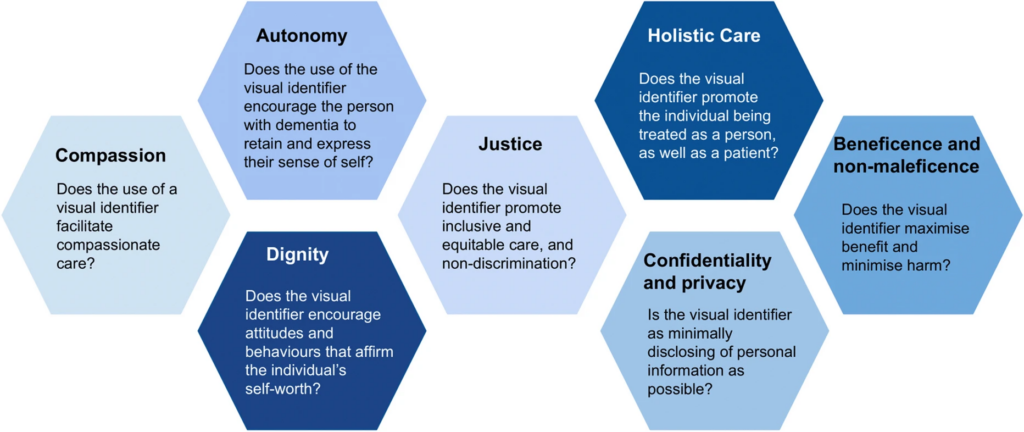

From this, we took the common themes, tensions and challenges we identified in the ethical and legal analyses and used those to help us develop seven key principles that could help inform the development and implementation of visual identifiers in future.

What we found

We identified seven key principles:

- Compassion

- Autonomy

- Dignity

- Justice

- Holistic care

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Beneficence and non-maleficence

These principles need to be considered at the same time, but it’s not possible to prioritise all of them simultaneously. Sometimes, they will overlap and reinforce each other, for example when an action which promotes a person’s autonomy also maintains their dignity.

They may also conflict with each other at times, and trade-offs might need to be made in the context of the use of visual identifiers. Rather than seeing the principles as a hierarchy, where some are always more important than others, the trade-offs and moral issues that arise need to be considered anew in each individual case.

Our analyses highlighted frictions between the aims of a visual identification system – bringing attention to the specific needs of the individual – and important aspects of good clinical practice like maintaining confidentiality. There are also potential issues around consent, which can be even more complicated if the patient doesn’t have the capacity to decide for themselves whether they would like an identifier to be used.

Our proposed principles can be used to mitigate against potential harms, but as no one principle trumps another, the setting and context in which the visual identification system is embedded will need to stay central to these decisions.

One approach to ethical decision-making may be to adopt an approach such as person-centred care, which means that visual identifiers aren’t used in isolation but alongside complementary strategies to maximise their benefits and minimise potential harms. Other strategies might involve high-quality training on caring for hospitalised people with cognitive impairment and the use of identifiers for a wide range of hospital employee roles, including non-clinical staff, such as porters or cleaners.

As the empirical evidence regarding the use of visual identifiers, their benefits and harms is limited, it’s also important to note that these principles, and the questions that they pose, are not exhaustive, and must be interpreted in light of findings from subsequent research and the wider context of implementation. Further studies could help advance knowledge in this field.

Key principles