Lindsay, R., Bridson, E., Greig, A., Lawrie, M., Scott, J., Watt, A., Hardy, S., Jones, B., Tallack, C., & Dixon-Woods, M. (2025). A framework to guide early planning of large-scale change programmes in health and healthcare. THIS Institute. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.123407

A framework to guide early planning (“the front end”) of large-scale change programmes in health and healthcare

Why was this framework developed?

The “front end” of large-scale programmes – the very early stages of designing and planning— is often where things can start to go wrong. This framework prompts the questions that need to be asked right at the beginning, offers some suggestions on what good looks like, and highlights learning from previous programmes in health and healthcare.

How was this framework developed?

The framework was developed through a collaboration between THIS Institute, the Health Foundation, and Ipsos using a multi-stage process. The first step involved review of research literature and national guidance on big programmes in both healthcare and other sectors (see Annex 1), followed by interviews with people who had previously led major change programmes in the health and social care sector.

You’ll see some quotations from those interviews throughout the report. A draft version of framework was put through an online stakeholder consultation. The final step was testing, using an in-person exercise with five policy teams.

Who is it for?

Who is this framework intended for?

This framework is intended for people who are designing large-scale change programmes in the health and healthcare sector, defined as follows:

A complex change programme in health and healthcare is a set of inter-related interventions and activities that are organised around a high-level goal or theme and that need to be directed and coordinated as a whole on a large scale.

Are there examples of large-scale health and healthcare programmes?

Historic examples include Virtual Wards, Community Diagnostic Hubs, the National Cancer Programme, the National Elective Recovery Programme, and the Elective Surgical Hubs programme. Looking ahead, the NHS 10-year Plan (2025) includes examples of future large-scale programmes where this framework is likely to be useful.

What drives these programmes?

Programmes may have multiple origins — for example, driven by political priorities, public concern, or a need for cost-saving, improvement, or standardisation. The framework recognises that such programmes are shaped by a complex mix of centralised authority, devolved decision-making, and intense political and public scrutiny.

What challenges do programme teams face?

Power and influence may be widely diffused across government departments, NHS bodies, professional groups, and regional organisations, posing often delicate governance and accountability challenges. The health sector’s scale, budgets, and institutional and legal structures add further complication.

How can this framework help?

In this complex landscape, where political influence can significantly shape programme direction and pace, this framework seeks to support programme teams in the early stages of designing and planning large-scale programmes, so they can better navigate these dynamics and benefit from prior learning.

Many of the questions are also relevant for those planning large-scale initiatives in health more generally, even if not on a national scale.

Testing during development suggests that the framework can be used flexibly and in ways that suit individual teams, but is likely best used as part of team-based conversations. A chair or facilitator may be helpful, especially if there’s more than a few people. In meetings, using printed versions of the framework can be useful so it’s easy to see as a whole and so you can flip backwards and forwards as the conversation unfolds.

Some strategies you can use:

- At a glance: Review the “at a glance section” to choose priority areas.

- Meeting planner: Use the questions to shape agendas for programme planning meetings.

- Skim and select: Scan the framework and highlight areas for discussion or knowledge gaps.

- Discussion prompt: Use the framework to guide questions to promote shared knowledge and understanding of the programme within the team.

- Step-by-step: Work through each section for a detailed review.

- Assurance tool: Evaluate or test some thinking or planning against the framework. Outside of a meeting, one possibility is to use AI to check your plan against the framework.

When should it be used?

The framework is designed for early programme planning, but can also be of value in reviewing and evaluating plans that are further down the road. It is particularly useful when many aspects of a programme are still uncertain or evolving — it does not assume certainty or fixed decisions.

In the early stages, the questions in the framework are likely to stimulate discussion and provide an aide memoire for important issues, but it probably won’t be possible to answer all of them. It might be helpful to highlight unanswered questions, and to identify a point at which selected questions will be revisited later in the programme.

The framework is not intended to replace programme management methodology, which remains critically important to success.

How long does it take to use?

The framework is divided into three sections and has 14 core questions. How long it will take to work through the framework in conversation will depend on programme maturity and complexity, so the chair/facilitator should discuss timings and allow flexibility for deeper discussion if needed.

- If it’s at the very earliest stage and no programme parameters have been defined (e.g. case for change, scope, boundaries and programme goals have not been discussed), you might need to allow significant time for the first section – perhaps a half day. The other two sections might take an hour to two hours each.

- If some progress has been made and some programme parameters have been defined (e.g. case for change, scope, boundaries and programme goals have been discussed in prior planning meetings), a half day for the whole framework might work.

- If the framework is being used to plan and scope future planning meetings, or to review existing programme plans, allow 90-120 minutes to review the whole framework and identify questions which have not been addressed.

Programme purpose and content

1.1 What is the case for change?

1.2 Is a large-scale programme the right approach?

1.3 What are the goals and the scope of the programme?

1.4 How will possible change solutions be identified, considered, developed, and tested?

1.5 How will the theory of change for the programme be developed?

2. Contexts, stakeholders and implementation strategy

2.1. What is the implementation strategy, and does it account for the programme’s context and strategic goals?

2.2. Is there a good understanding of the environment in which the programme will be implemented?

2.3. What is the approach to stakeholder engagement, and how will it support programme success?

3. Programme management, costing and scheduling, governance, and learning

3.1. What programme management methodology will be used, and is it fit for purpose?

3.2. What governance structures will be established to provide day-to-day oversight and accountability?

3.3. What overarching governance, leadership and management structures will be in place?

3.4. Is costing and scheduling sound and realistic?

3.5. How will risks be identified, anticipated, and managed throughout the programme?

3.6. What are the plans for monitoring, evaluation, and learning, and how will they inform continuous improvement?

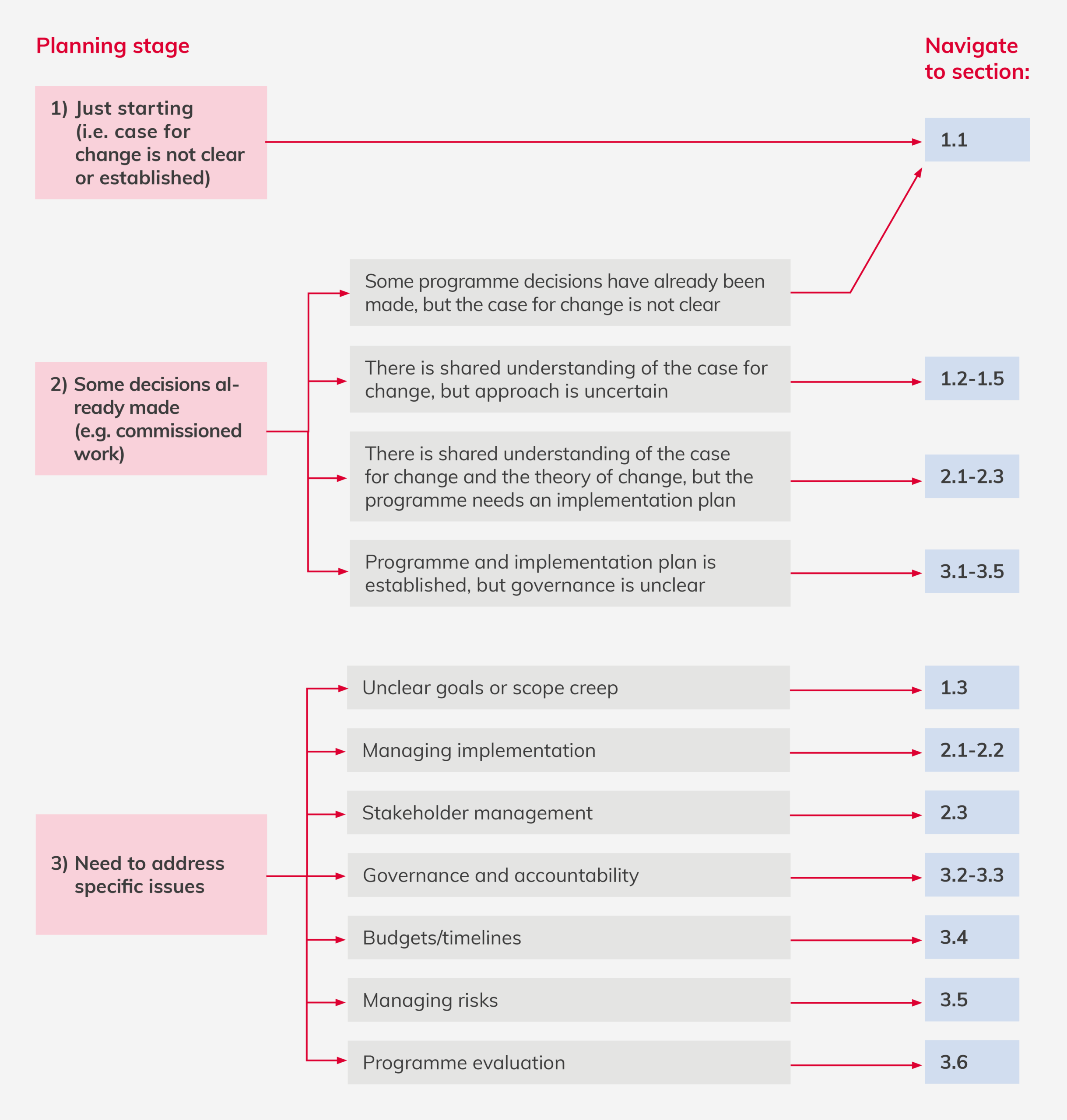

The framework is presented in linear stages to help navigation, but it can be used iteratively and flexibly, as part of conversations in the very early stages of planning a programme. If it is not clear where to start, the decision tree may help in quickly navigating to the most relevant sections based on the programme’s current situation, time constraints, and specific challenges.

Click the image to view in full screen.

Programme purpose and content

1.1 Core question: What is the case for change?

Prompt questions

-

- What is the strategic rationale for a change programme?

- What is the policy context, including national visibility, scrutiny, or controversy?

- What is the political context, including the influence of short-term government priorities, and the role of ministers and Treasury in shaping programme scope and expectations?

- What is the public’s experience of the issue (e.g., Urgent and Emergency care waits, difficulties getting a GP appointment, access to dentistry), and how does it vary across different groups?

- How do different stakeholders understand the problems or opportunities to be tackled, and to what extent is their understanding aligned?

- How will you secure a unifying vision that secures political support while also being credible and motivating to frontline staff?

- What evidence supports the need for this programme?

- What evidence supports the value the programme is expected to deliver?

What good looks like

-

- The origins and imperatives for change are recognised and understood, along with the context (e.g. political, advocacy) that has brought the problem or opportunity to be addressed to the fore.

- The nature, scale and severity of the problem to be addressed has been soundly characterised (e.g. poor performance; evidence of unwarranted variation or inequities; inefficiencies; inadequacies in service models or service cohesion; opportunities offered by emerging technologies or clinical evidence to improve care or reduce costs; changing demographics and workforce, etc).

- Sufficient time and resources are allocated to gather and analyse data and evidence to engage in consultation about the problem to be solved or opportunity to be grasped, including with sponsors, government and delivery stakeholders.

- Diverse stakeholder perspectives on the case for change are identified and taken into account in planning.

- Pressure (including political or public) to get started quickly is managed to enable clear understanding of the case for change.

“The first step in my mind is, is there a problem? What is the problem? I had a one- to-onewith [the Prime Minister of the time]. He asked me five questions. Is [this issue] as bad as people make out? Why is it so bad? What are you going to do about it? How long will it take, and what will it cost? He wasn’t at that stage interested in all the answers, but he was interested in [whether I could] articulate what the problems were and therefore what I might do about them.”

“Making sure that your narrative can pivot as quickly as it needs to [to] make sure that you can still demonstrate the case for change and why it’s important to new people with different priorities.”

“We tend to do it on the basis of political will too often rather than actually [whether] it’s a priority. So Secretary of State says we must do, and therefore we do it rather than say, actually, Minister, you’d be better off doing something different.”

1.2 Core question: Is a large-scale programme the right approach?

Prompt questions

-

- Is a large-scale programme approach well matched to the case for change, or could similar outcomes and impacts be achieved through a more locally driven, bottom-up approach?

- What is the role of national direction, standardisation, coordination, and resource investment in addressing the case for change?

- How will delivering at scale enable efficiencies and better outcomes (e.g. through shared infrastructure, procurement, or service delivery mechanisms), and to what extent could these be achieved through local arrangements without a nationally mandated programme?

- In what ways are centralised levers such as a national mandate, policy, incentives, standards or guidance, government resources or regulatory authority likely to be important to delivering the outcomes?

- What is the evidence that local areas would struggle to fund or deliver change effectively without national direction and/or support?

- Where the case for a large-scale national approach is uncertain, incomplete, or contested, how can the programme team test assumptions and feedback concerns or alternative options to sponsors or government?

What good looks like

-

- The changes sought are system-wide, national-level changes with the aim of producing collective impact, perhaps on outcomes across settings that may be highly variable.

- Evidence, analysis or consultation demonstrate the advantages of scale, perhaps based on similar previous projects.

- There is a strong case that national direction, leadership and coordination will maximise return on investment and potential for impact.

- The political context has been assessed for favourability to a large-scale programme approach, recognising that governments typically seek to balance control and flexibility over electoral cycles.

- There is recognition that large-scale change requires time to establish and embed, and it’s been established that a programme timescale is acceptable to political and health systems leadership.

- Plans for sustainability of funding, leadership backing, and staffing are robust enough to withstand potential shifts in political or health system leadership over the programme lifecycle.

- Governance structures are in place that enable programme teams to interrogate assumptions and, if needed, challenge government or sponsor decisions in a constructive way.

“Single individuals do not have decision-making capability for the decisions that matter because we are in an inherently political environment. The executive and ministers are going to want tobe involved in those conversations.”

“These big national programmes, they probably need to be relatively bounded, they probably need to be relatively clear on the population that you’re tackling something for and they probably need to have fairly clear objectives.”

1.3 Core question: What are the goals and the scope of the programme?

Prompt questions

-

- What are the strategic objectives, scope of work, and benefits sought?

- What is the strategy for determining which outcomes and impacts are expected for whom and by when?

- In what ways do the programme’s objectives align with each other?

- Where might there be tensions and trade-offs?

- What benefits or outcomes might be important, even if they are difficult to quantify?

- How do the programme’s goals reflect political priorities, and how might they need to adapt to shifting ministerial or Treasury expectations?

- How have issues of equity and equality been considered?

What good looks like

-

- The goals and scope of the programme are clearly defined and aligned, so that ambiguity about what it is intended to achieve within what boundaries is reduced, even as political priorities evolve.

- The intended benefits, outcomes and impacts are clearly described, along with identification of the groups likely to benefit and analysis of equity implications.

- There is a clear prioritisation of the intended benefits of the programme (e.g. primary and secondary intended benefits).

- Benefits that might not be easily measurable in numerical or financial terms (e.g. improvements in staff morale) are recognised.

- The possible trade-offs and tensions between the different goals of the programme are recognised and a plan is in place for managing them.

- A programme lifecycle approach is used, with a provisional timetable for achieving the benefits that accounts for political cycles, funding windows, and the need for adaptability.

“The other mistake we make is to say there are 100 problems to fix in [this area of health and care], so let’s have a programme that addresses all of them. […] It’s not going to happen. So what are the 10 most important? Let’s do those and then move on.”

“Objectively [this programme was] successful, but it was also working with a subset of a population of probably [approximately half a million] people. So you can put your hands around it, you can deal with it.”

1.4 Core question: How will possible change solutions be identified, considered, developed, and tested?

Prompt questions

-

- How will different options for the solution, including those that extend beyond what currently exists, be identified?

- What will you do to actively seek out innovative approaches, and how will you adjust your evaluation process, so they are fairly judged alongside more conventional options?

- What methods will be used to manage risks of escalating commitment to a particular solution (e.g. following initial scoping, identification, testing or piloting) especially when there is political or ministerial pressure?

- How will the risk that solutions might be unfairly influenced by the ambitions of specific stakeholder groups be considered?

- How will the potential solutions be assessed and tested, who will be involved, and what methods and criteria will be used?

- In what ways does the clinical or technical evidence support the potential solution, and where are the gaps?

- How will the impacts of the solution across different regions, social groups, or demographic areas, including the potential to influence health inequalities, be assessed?

- At each decision stage, how will the work done give assurance that the change solution selected is the right one?

- What confidence is there that if the change solution is implemented in a well-designed programme, it will make a material contribution towards solving the problem or advancing the opportunity?

What good looks like

-

- A structured but agile approach to generating possible solutions is used.

- What worked and what did not in previous similar programmes is used to guide thinking about candidates for the change solution.

- Commitments to specific solutions are not made too early, even when there is political and/or time pressure to get going quickly.

- A plan for long-listing, short-listing, and feasibility and affordability analysis is in place.

- Possible solutions are assessed using clear, predefined criteria, including cost- effectiveness, clinical evidence, and stakeholder feedback.

- Solutions are assessed for their potential to reduce or exacerbate health inequalities, ensuring fair access and outcomes across all demographic groups.

- When a solution is new, unfamiliar, or hard to understand fully, appropriate simulation, prototyping and piloting is undertaken across different contexts, with attention to the need for a solution that is scalable and spreadable.

- The potential unintended positive or negative outcomes of the proposed solutions are identified.

- The proposed solution maps well onto the problem and problem drivers or opportunity that motivated the programme, while recognising the political context.

- Relevant stakeholders (e.g. clinical professionals, health service managers, patients and carers) are engaged at key decision points to ensure acceptability and implementability.

- The external dependencies and interdependencies (e.g., funding, political climate, technology) that may impact the success of the solution are well understood.

“If you get a crisp articulation of the problem you’re trying to solve, the right thing to do is then to move resources onto that problem, give them time to understand it, to articulate it, to do a proper options appraisal and to come back with an assessment of options. And those have to be genuine options.”

“Don’t go out to people and say what should we do? […] Go out with a skeleton and say here’s what we think, that we genuinely want your opinion, and change it according to what they say. But give them something to argue against or for […] which when you then say, please do it, they recognise it.”

1.5 Core question: How will the theory of change for the programme be developed?

Prompt question

-

- How will the theory of change* for the proposed programme be developed?

- How will political priorities, ministerial expectations, and Treasury requirements shape the theory of change?

- Have relevant legal, ethical, and social factors been considered and incorporated into the theory of change?

- What possible unintended consequences can be anticipated?

- How will the decision on the right balance between national-level standardisation and local flexibility be made?

- How will the theory of change be iteratively operationalised and tested, and what decision points will be built in to respond to evolving political and stakeholder contexts?

What good looks like

-

- Visual or narrative representations of the programme theory of change are developed and accessible to stakeholders, including government and those implementing the programme.

- The theory of change is informed by the available evidence, including clinical evidence where appropriate, and by relevant disciplines (e.g. IT, human factors, supply change management etc) and by frameworks on implementation and improvement.

- The theory of change is informed by engagement with the relevant stakeholders, including clinical professionals, service managers, and patients and carers.

- It is clear what elements of the programme will be standardised and what will be suitable for local customisation, and the rationale for degree of standardisation is clear.

- Variability in local capacity and capability has been accounted for in the theory of change.

- A plan is in place to test the theory of change with stakeholders, for example, using simulation/prototyping, consulting, and piloting across diverse contexts.

- Mechanisms are in place to enable continuous improvements to programme design during the implementation phase (e.g. governance, feedback loops, culture within the team etc.)

* A theory of change is a representation, often visual and accompanied by a narrative explanation, of programme’s key components, illustrating the pathway from activities and interventions to the intended outcomes. It clearly identifies the indicators used to measure outcomes and explains the underlying causal mechanisms and assumptions that link actions to outcomes. In brief, it explains what the programme seeks to achieve and how.

Further guidance can be found here.

“So let’s actually make sure that we understand what’s our logic model, what are the benefits? How are these things going to achieve not just productivity benefits, but savings in the NHS and/or reduce the time spent on this so that we can achieve, of course, what we’re all trying to achieve, which is the outcomes for humans.”

“Making sure that your narrative can pivot as quickly as it needs to [to] make sure that you can still demonstrate the case for change and why it’s important to new people with different priorities.”

Contexts, stakeholders and implementation strategy

2.1 Core question: What is the implementation strategy, and does it account for the programme’s context and strategic goals?

Prompt questions

-

- What framework could guide the implementation strategy for the programme (e.g. implementation science and suitable framework for spread and scale)?

- What delivery system will be used for the programme, and what criteria will be used to select it?

- What levers (e.g. regulation, financial incentives, behaviour change strategies, performance management strategies) can be used to ensure the programme is implemented as intended?

- Are the levers likely to be sustainable and effective in the long-run, especially in the face of changing government agendas or funding cycles?

- What workforce, roles and staffing will be needed, and is there sufficient workforce with the necessary skills to meet programme needs?

- How will collaborative mechanisms (e.g., peer learning groups, communities of practice, critical friends) be used to support participating organisations and individuals?

- How has patient experience and access been considered?

- How will the risks of escalating commitment be managed after the programme is launched?

What good looks like

-

- The implementation strategy is based on relevant evidence for the type of programme.

- The need for an effective delivery system is recognised and clear criteria are used to guide its selection.

- The implementation strategy offers clarity on key decisions, such as a “scale and spread” model (gradually across different sites) versus a “big bang” (all at once) approach.

- Flexibility is built into the delivery and implementation strategy to accommodate evolving political priorities, stakeholder engagement, and operational realities.

- The implementation and delivery strategy effectively supports the goals outlined in the theory of change.

- National and local responsibilities for implementation are clearly defined and structured for collaboration.

- The levers to be used in the programme are designed to achieve programme benefits, not simply demonstrate compliance.

- Unintended consequences of the proposed levers been assessed.

- Evidence-based strategies are planned to facilitate change.

- Social movements, networks, and partnerships are actively recognised as part of the programme’s infrastructure.

- Existing initiatives (e.g. professional or community networks) are leveraged rather than reinvented.

“There was a big stick and don’t underestimate the stick. […] If you get it into the Health and Social Care act, and that’s part of your regulation, you’ve got a regulatory framework to beat someone over the head with if they don’t do it.”

“We ran roadshows where we’d like, okay, so you’ve already got this, you’ve already got this, you haven’t got this, you need to fill that blank. We wrote how to guides, we wrote exemplar guides, we did workshops, we did learning networks, we did shared celebration things. We had a national way of tracking this so people didn’t have to worry about that at local level.”

2.2 Core question: Is there good understanding of the environments in which the programme will be implemented?

Prompt questions

-

- What sites will be involved, and on what basis, and how will they be engaged?

- How will you assess whether local organisations (e.g. trusts, hospices, practices, neighbourhood teams etc) have the capacity and skills to implement the programme?

- How will you support local organisations that do not have the capacity and skills to implement the programme?

- What complexities are likely to arise from the nature of the organisations or sectors that are involved in, or targeted by, the programme (e.g. GP practices, local authorities, Integrated Care Boards, NHS trusts, regulators, professional bodies, arm’s length bodies, third sector and patient-led groups etc.)?

- How will the programme assess whether organisational and institutional cultures, such as those at local sites or across professional and system levels, support its success?

- How will the power dynamics and the influential actors in the system be identified?

- Is there a training plan in place, specifying which processes will be targeted, the resources that will be required, and the expected impact?

- What strategies will be put in place to manage change fatigue among those implementing the programme on the ground?

What good looks like

-

- Key contextual factors which could influence the programme are identified and managed, including:

- Regulatory and policy frameworks (e.g. NHS guidelines, professional standards, health policy etc.)

- External dependencies and interdependencies

- Institutional contexts (e.g. restructuring, recruitment freezes, training structures, buildings and facilities)

- The complexities of the health ecosystem, including its professional hierarchies and political sensitivities, are recognised and planned for.

- The organisational, technological, work system design, and behaviour change that will be needed for the programme to be implemented have been identified.

- A plan for tailored capacity-building support is in place to address identified gaps in knowledge or resources.

- The potential tensions between the programme priorities and other priorities are recognised and a plan is in place to manage them.

- Plans for implementation account for local variation in capability, capacity and readiness.

“The stakeholders, you have to understand really carefully because they all have their self-interest, but it’s about being bigger than that. It’s about thinking about Venn diagrams. What is the big Venn diagram that contains everyone’s interests in this area and furthers everyone’s ambitions?”

“You have to have the ear of all of the clinicians in England as well as the general public and government.”

2.3 Core question: What is the approach to stakeholder engagement, and how will it support programme success?

Prompt questions

-

- What is the compelling, unifying vision of the programme that stakeholders can get behind?

- What approach has been taken to ensuring the inclusion of patients and carers and civic society groups as key stakeholders?

- How will the programme ensure appropriate attention is given to seldom heard and disadvantaged groups?

- What are the non-monetary sources of influence that are likely to be important to the programme?

- How have the realities of professional dynamics (e.g. different professional groups and interests) in the health service been considered and planned for?

- How will buy-in be secured from people who will be influential in making the programme work, and those who could be influential in disrupting it?

- What tensions might arise between stakeholders, and how will they be mediated?

- What mechanisms exist for iteratively adjusting the programme based on stakeholder feedback and other learning?

- How will trust be built and maintained among stakeholders, and how will it be assessed?

- How will the communications strategy to facilitate change be developed?

What good looks like

-

- A clear plan for identifying and engaging stakeholders.

- Clear understanding of the role each stakeholder expects to have in programme design, delivery and implementation.

- Stakeholders’ levels of power, influence, and any vested interests, including political, professional and reputational, are mapped and understood.

- Stakeholder engagement is meaningful, inclusive, and informs decision-making throughout the programme lifecycle, but is managed carefully to ensure clarity of purpose.

- A clear and unifying strategic vision for the programme is communicated.

- Formal (e.g. structured stakeholder engagement groups) and informal (e.g. informal catch up discussions) structures are in place to enable ongoing feedback from stakeholders.

- Messaging is tailored to the needs, interests, and language of different stakeholder groups, including political actors, clinicians, and the public.

- Communication supports understanding, buy-in, and alignment across all levels of the system.

“The collective vision. Hugely important. And even after you’ve published a strategy, you need to go on and on and on about that. As part of our project we used to meet with them three times a year, face-to-face, and actually generate that collective vision.”

“I find getting stakeholders to be in the room with each other to thrash some of this stuff out is essential to actually getting that coherent view”

“Let everyone come into the tent, let everyone be heard, a flat hierarchy is really important.”

-

“Securing money from the treasury requires you to act in a certain way […] then there is how you actually deliver that into the NHS front line, which is different. You might talk about oranges, apples and pears to the treasury, but fruit salads and trifles to the NHS.”

Programme management, governance, costing and scheduling, and learning

3.1 Core question: What programme management methodology will be used, and is it fit for purpose?

Prompt questions

-

- Does the programme sit in a portfolio of programmes, and if so, are similar programme management methods being used across the portfolio?

- How will the programme join up work with other programmes, so that people on the ground are not getting conflicting or competing guidance, priorities, instructions, or timelines?

- Are the specific characteristics of large-scale projects, including their risks, complexity, scale, and duration, fully accounted for in the programme management approach?

- How will it be determined when a decision is needed on whether the programme remains affordable and practical to continue, and how will it be communicated to government, sponsors and those implementing the programme?

- Is there a defined exit or transition plan, including how the programme will link with or hand over to other programmes?

What good looks like

-

- Those designing and planning the programme are familiar with relevant government guidance (e.g. the Teal Book on project delivery and management), using it to inform the design and planning process.

- An established (not an ad hoc) programme methodology is used, and any amendments to the methodology are made intentionally.

- Programmes within a portfolio share a broadly similar programme management approach.

- There are enough runway and sufficient decision-making check-points, with the right scrutiny, to ensure that the programme does not proceed to delivery too soon.

- Exit and transition plans are designed to ensure continuity and sustainability, even if political attention or funding shifts, with clear communication strategies for stakeholders at all levels.

“Not everything will work the way that it is intended. Building that into your cost models, your culture and your governance [is important] so that you’re not stuck delivering something which is not going to do what you thought it was going to do.”

3.2 Core question: What governance structures will be established to provide day-to-day oversight and accountability?

Prompt questions

-

- How is governance designed to ensure that the programme is optimally configured to achieve its intended benefits within the expected timeline?

- Who will be responsible for oversight and accountability of the programme in the long run, and how will this be managed?

- How will it be clear that those charged with governance have the right experience, skills, and knowledge, including political astuteness, to be able to challenge and make decisions on the project?

- How will an integrated assurance plan that supports long-term financial planning and clearly identifies reporting needs, timelines, and formats be created?

- What is the system for allowing the programme team, the sponsor, the programme board and wider stakeholders to provide feedback on whether the level of reporting and control is too much or too little?

- What are the systems for learning about concerns about the programme and acting on them?

What good looks like

-

- Appropriate mechanisms of accountability and oversight are in place to ensure the programme is properly monitored and held to the necessary standards.

- Those overseeing the programme have the right kinds of expertise, including clinical knowledge, technical competencies, and political awareness where needed.

- Those overseeing programme management understand their role is to focus on strategic outcomes, not just delivery.

- Those overseeing the programme add value through informed, competent, strategic questioning in good faith.

- The programme team includes a broad range of backgrounds and experience.

- A culture of trust and constructive challenge exists between the delivery team and the sites, and between those teams and the team overseeing programme management.

- Clear decision-making points are built into the programme lifecycle (e.g. approval gates, assurance reviews).

- Reporting is meaningful and streamlined (e.g. limited, relevant KPIs and “intelligent reports”).

- Governance structures support flexibility and honest discussion, not just compliance.

- Governance arrangements are designed to adapt as the programme changes (e.g. as power is devolved from central to local organisations).

“Where do you govern the out-of-scope dependencies for a programme because not everything is within your control. When you are cutting and re cutting the scope of a programme, it’s how you govern those decisions. A strong delivery model has enough governance that joins it up with the wider organisation, its wider operating model, rather than trying to exist in isolation.”

“What my technocratic targets are, versus, are we making the progress that we want to be making is a really important distinction to make.”

“There’s a lack of empowerment and we tend to wrap ourselves up in governance to convince ourselves we’re doing the right thing. But in actual fact, if we had much less of it, we’d save a whole heap of time.”

3.3 Core question: What overarching governance, leadership and management structures will be in place?

Prompt questions

-

- Has learning from the National Audit Office on governance and decision-making on mega-projects been considered in the design and planning of the programme?

- Is there clarity about the leadership qualities needed for the programme, including clinical, technical and political, competencies where appropriate?

- How will delivery, affordability, and value be at the forefront of decision-making?

- What is the optimal team composition for leading and managing the programme given its goals, content, and context?

- What combination of skills (e.g. leadership, operations management, clinical, evaluation, procurement, technical, political navigation, etc.) will be needed by the programme team?

- Is there likely to be a need for external consultancy or suppliers?

- What might be the challenges in recruiting the leadership team and the site teams (e.g. release from clinical roles etc)?

- What is the plan for enabling the team and leadership structure to be changed as the programme develops, should that be needed?

- In what ways are the planned governance systems designed to respond to unanticipated events and difficulties?

What good looks like

-

- Governance design takes account of lessons learned from reviews of major government projects.

- Roles and responsibilities for decision-making are clearly defined to ensure accountability and effective governance, and are communicated across the team.

- A suitable named person with the right leadership qualities is responsible for leading the programme.

- The programme leadership team has the skills and abilities to navigate and manage key political and other stakeholders across the health ecosystem.

- If important for the programme, the right clinical expertise is built into the programme leadership structure and teams.

- Programme leadership has the ability to communicate, engage and motivate across the programme.

- The governance design can accommodate different skills and expertise that may be required of leadership teams and governance structures at different phases.

- Governance systems are specifically designed to include the ability to react to issues while maintaining control over scope, cost and schedule.

“Being very clear who is accountable and […] for what […] and the purpose. [e.g]. The ministers, who are accountable for getting stuff done on the ground, how the two leadership roles (the SRO and the programme director) work together, that’s really important.”

3.4 Core question: Is costing and scheduling sound and realistic?

Prompt questions

-

- What might affect planned timelines and resource allocations, and how might any challenges be addressed?

- What costing methodology will be used to determine the budget, and how does this align with expectations from government?

- How will economic modelling be used?

- Are the uncertainties (e.g. relating to complexity, novel design or innovation) accounted for in the design, cost forecast and probable delivery date of the programme?

- Will a range-based approach be used to indicate estimates around uncertainty?

- How will the programme team manage the risk of budgets and timelines being made public too early, before the options, costs, feasibility, and ability to deliver have been fully assessed?

- How will procurement practices, supplier arrangements and contracts be structured to drive success?

- How will suppliers that do not deliver or who fall behind be held to account?

- What assurance or evidence is there that the programme will be sustainable in the long run?

What good looks like

-

- Costing is based on a recognised methodology.

- Ranges are used in reporting estimates of costs and scheduling to indicate uncertainty.

- The risk of committing too early to budget and schedule is recognised and managed.

- Historical data from similar programmes is used to inform cost and timeline estimates where appropriate.

- Potential changes over time (e.g. policy shifts, demand, supply) are considered in resource planning.

- Opportunities for cost savings associated with large-scale delivery are identified (e.g. productivity investments, procurement at scale, shared learning).

- Contract types (fixed-price vs flexible) are chosen appropriately for different suppliers.

- Any delivery partners follow standard practice as specified by the programme.

- National monitoring processes for procurement practices are established and agreed, and suppliers are held to account as appropriate.

“What is the control of funding? [This national programme] committed several hundred million but didn’t have strong levers to make sure that that actually got where it was needed.”

“The bigger your organisation, the bigger the portfolio, the longer it can take you to get a decision made. So I think some of that comes back to the budgeting bit and the prioritisation is this priority. I think that our decision making in a […] large, complex portfolio, could be too slow, and we don’t delegate decision making sufficiently to achieve success.”

3.5 Core question: How will risks be identified, anticipated, and managed throughout the programme?

Prompt questions

-

- How will the potential risks to the programme be identified, including through systematic analysis and “soft intelligence”?

- Have the known risks of large-scale programmes (see Annex 1) been considered systematically?

- How will cultural challenges that prevent organisations and programmes meeting best practice (e.g. culture, egos, internal politics) be managed?

- What methods will be used to monitor risks once the programme is underway?

- What adaptive capacity will be available to respond to emerging risks?

What good looks like

-

- Sufficient time and resources have been allocated to assess the risks (broadly conceived) before the programme is implemented.

- Potential risks, both broad and specific to implementation, are identified and a plan is in place for their management prior to full programme roll out.

- There are mechanisms to track and respond to unintended consequences once the programme has been rolled out.

- Known risks of large-scale programmes are considered and addressed (see Annex 1).

- Programme teams are supported to engage in honest dialogue with sponsors about risks, including those that may be politically uncomfortable, with governance structures that enable constructive challenge and adaptation.

“Formal governance processes are there and they help, but I think it’s really important to be honest and not just bring glowing reports that everything’s fine. You have to say these risks are real, these things are happening, and be honest about that.”

3.6 Core question: What are the plans for monitoring, evaluation, and learning, and how will they inform continuous improvement?

Prompt questions

-

- When will an impact, process, and economic evaluation of the whole programme be undertaken, and has it been costed for – including consideration of political timelines and reporting expectations?

- What type and “character” of evaluation (e.g., rapid-cycle, formative, impact, process, economic) will be used, and how does it align with programme rollout (e.g., phased scale-up vs. all-at-once “big bang” implementation)?

- Has the risk that possibilities for evaluation might be closed down by decisions taken early in the programme been considered?

- Are there agreed measures of success, will the data be available, and is data collection and analysis capacity in place?

- What are the plans for monitoring programme delivery and performance?

- What indicators will be used to assess the health of the programme beyond delivery outcomes, including stakeholder relationships, collaboration, engagement, and political support?

- What strategies will be implemented to ensure continuous learning?

- How will the impacts of the programme on health inequalities be assessed?

What good looks like

-

- People with evaluation expertise are engaged from the start to ensure that planning for programme design runs in parallel with planning for evaluation.

- Early decisions on the evaluation approach and timing of key learning points are made to ensure robust impact evaluations can take place, even under political pressure for quick results.

- Strategies are in place to foster transparency and learning during the planning and delivery phase (e.g. critical friends who provide constructive feedback).

- Short-term deliverables and long-term outcomes are clearly identified, and a small number of evidence-based indicators are attached to them.

- Clear systems and support are in place for monitoring at both local and national levels, with reporting tailored to the needs of different audiences including government and those implementing the intervention.

- Data collection plans are defined, with clarity on what data will be collected and why.

- Data is relevant, purposeful, and used to inform decision-making and demonstrate progress, with clear patient-centred and clinical relevance where applicable.

- There are clear strategies for tracking and managing unwarranted variation.

- Monitoring is proportionate and aligned with the programme’s goals and scale.

- Plans are in place for sharing data and progress with specific stakeholders at key points, and for wider public dissemination.

“You’re only as good as that last graph. So it is constant. The pressure is always on to make sure we’re delivering.”

“After each deliverable, we have a quick after-action review just to see if there’s any course directions that we need to make. And then at the end we have the retrospective that enables us then to go into the next one. Building on, building on that. And that was quite a well tried and tested mechanism.”

Annex 1: Known causes and cures of poor mega-project performance, adapted from a systematic review by Denicol et al. (2020)

Denicol J, Davies A, Krystallis I. What are the causes and cures of poor megaproject performance?

A systematic literature review and research agenda. Project Management Journal. 2020 Jun;51(3):328-45.

This annex draws on Denicol et al. (2020), a systematic review of mega-project performance.

Providing a well-evidenced and cross-sectoral overview of common pitfalls and success factors in large-scale initiatives, many of its themes are directly applicable to health and healthcare programmes.

1. Decision-making behaviour

Causes

Optimism bias refers to the human tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive outcomes and minimise the likelihood of negative outcomes. A common phenomenon in project planning, optimism bias leads to over-estimation of the benefits of a project and underestimation of costs and time to implementation.

Strategic misrepresentation arises from misalignment of incentives, and involves manipulation aimed at getting a programme funded and underway. Diverse pressures (political, organisational, and individuals) may result in a distorted and misleading version of the situation (e.g. involving an unrealistically low budget, short timescale and claimed benefits) at the outset.

Planning fallacy describes how biased judgement and advice that leads to underestimating costs, ignoring risks, and overclaiming benefits.

Escalating commitment: once started, a programme may be seen as too big to fail or too costly to stop, so resources keep being allocated to it even when there is evidence it is not working well.

Cures

- Use learning from previous similar projects to identify what worked and what didn’t, and to benchmark and see what can be improved.

- Anticipate and plan for uncertainties, since large projects are subject to constant change.

- Put significant time and energy in upfront to enable scrutiny of and prevent biased thinking.

- Be alert to the possibility that the information and advice being provided to the project may be flawed or biased, and be prepared to challenge or even impose penalties for misleading information.

- Monitor for opportunistic behaviour.

- Build in options to defer decisions and progression to enable further assessment of risks, economic viability, and over-commitment.

- Be alert to the political context of the project.

- Invest resources in the pre-construction phase and use it to generate learning and provide the basis for decisions.

2. Strategy, governance and procurement

Causes

Inadequate definition of roles and responsibilities, including those relating to who identifies the goals of the programme, who is responsible for design and who is responsible for implementation on the ground. Without a long-term vision and clear definition of roles, those promoting the programme may try to transfer the risk to the suppliers or delivery partners.

Poor governance describes the design of governance and its flexibility to adapt as the programme evolves, including the balance between hard (e.g. policies and legal requirements) and soft (e.g. relationships between national teams and local services) forms of governance.

Weak delivery model strategy, including mechanisms to procure capacity and capability from external suppliers (e.g. technology or pharmaceutical suppliers) that result in transactional and adversarial relationships in the supply chain rather than integrative and collaborative ones. For example, contracts may prioritise short- term costs, rather than fostering long term, collaborative relationships.

Cures

- Clarify the different roles and organisations in the project (e.g. sponsor, client, owner) and ensure they are not antagonistic.

- Be clear about the strategic objectives and scope of the project.

- Design a governance system that covers the whole project delivery chain.

- Put informal governance mechanisms in place to support the informal ones.

- Balance the risks across the supply chain and the various parties involved when selecting the project delivery system.

- Use integrated project teams that involve the key decision-makers along the delivery chain.

- Consider early engagement of any contractors.

3. Risk and uncertainty

Causes

Risks associated with technological novelty: The introduction of unproven technology leads to the programme costing more and taking longer than anticipated.

Challenges associated with flexibility occur when programmes struggle to adapt to unforeseen or evolving conditions such as changing population demographics, workforce changes, pandemics and disease outbreaks.

Challenges associated with complexity occur amid uncertainty around the interactions between various programme components, the organisation it is being implemented in, the wider health system, and the local environment in which the programme is being delivered.

Cures

- When deploying a technology, balance between re-use and novelty and between exploitation and exploration.

- Avoid concurrency (trying to do multiple things at the same time).

- Use technology, integrated work teams, project information systems, and digital models to improve communication.

- Maintain design flexibility and adaptability until as late as sensible in the decision making process.

- Ensure organisations are adaptive to change (e.g. with the right enterprise culture, HR and organisational structures).

- Use a project management approach that enables balance between flexibility and control to navigate the project’s multiple interfaces.

- Use modularisation to decrease complexity and to mitigate schedule deviations and increases in costs.

- Try to simplify where possible to keep complexity manageable.

- Use mutual adjustment strategies, since many mega-projects cannot be fully specified at the outset.

4. Leadership and capable teams

Causes

Weaknesses in project leadership: leadership fails to foster a collective vision and establish shared goals.

Weaknesses in competences: the programme team does not have the competencies or skills necessary to carry out the programme.

Weaknesses in capabilities: insufficient organisational knowledge to deliver each stage of the programme.

Cures

- Ensure project leaders are empowered, dedicated, and committed to its success.

- Develop corporate and project cultures that are underpinned by values of trust, collaboration, and safety.

- Manage differing perspectives to promote motivation toward common project goals.

- Invest in rapid staff recruitment and retention.

- Attend to human problems and actively manage conflicts to avoid them escalating into disputes.

- Use professional project management.

- Build project capabilities at multiple levels.

- Develop organisational abilities to nurture good relationships.

- Ensure organisational resilience and responsiveness throughout the project lifecycle.

5. Stakeholder management and engagement

Causes

Challenges in institutional context: poor understanding of the stakeholders’ interests and power dynamics.

Stakeholder fragmentation: a lack of alignment across the different stakeholder groups resulting from poor stakeholder management.

Challenges in community engagement: a lack of clear and consistent engagement with the local population who will be affected by the programme (e.g. patients, their families and staff).

Cures

- Ensure transparency in processes and criteria to minimise the possibility of corruption.

- Minimise the impact of political influence by embedding and aligning the project in the relevant institutional framework.

- Develop strategies to engage in projects with diverse dynamic institutional actors.

- Manage stakeholders, identifying their different drivers, interests, power, culture, resources, and expectations.

- Have regular meetings between the project manager and key executives.

- Invest in organisational structures for external interfaces with different entities in an evolving and temporary project

environment. - Use public outreach strategies, including campaign, to communicate with the public.

- Engage early with end users to capture ideas that will inform the design concept prioritise realisation of benefits.

- Promote local organisations in the supply chain and enhance their awareness of the importance of working collaboratively.

6. Supply chain integration and coordination

Causes

Weaknesses in programme management: inability to handle programme complexity due to insufficient processes and tools for effective monitoring and continuous improvement.

Challenges in commercial relationships: poor management of formal relationships between external providers supporting or delivering parts of the programme.

Challenges in systems integration: insufficient skills and capabilities to coordinate the suppliers providing services/resources for a programme.

Cures

- Ensure well-specified contracts and strong management processes to control and minimise changes to the baseline.

- Establish an accurate and consistent information management system that is able to adapt to different structures and data generated along the project life cycle.

- Involve engineering and project controls to monitor, detect, and control the impacts of cost underestimation, scope changes, and schedule deviations.

- Design procurement systems that encourage competition and are flexible enough to adjust when project conditions change.

- Design contracts and incentivisation mechanisms in the knowledge that programme participants will tailor their behaviour and relationships accordingly.

- Define metrics for performance measurement in the contract.

- Use the nature of the work to design the structure of project organisation.

- Design the integration of systems considering the multiple interdependencies (internal, external) of the programme.

- Use a coordination framework to manage integration in an environment with dynamic requirements from the network of suppliers.

The following resources can be used when considering the questions posed in the framework:

- Cambridge Elements series: Large-scale change programmes (due for publication Spring 2026). The Element series highlights the key literature and case studies from health research and mega-projects literature.

- Pre-print: Early planning (“the front end”) of large-scale complex change programmes in health (due for publication in early 2026). Combines health research and megaprojects literature, with insights from those who have experience running large-scale national programmes in the NHS.

- Improving the effectiveness of complex national service change programmes in health care: Report of findings from consultation interviews. Collates insights from interviews with 17 people who have experience in senior roles delivering complex national health care programmes.

- Large-System Transformation in Health Care: A Realist Review. Synthesises evidence on large-scale health system transformation, identifying mechanisms, contexts, and outcomes that enable or hinder successful change.

- The Teal Book on project delivery and management. Builds on the expectations of the Government Functional Standard for Project Delivery and serves as the core reference on how project delivery should be done in government.

- Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. Provides a structured process for designing, evaluating, and refining complex interventions in healthcare, with emphasis on theory, feasibility, and stakeholder involvement.

- The UK Government’s Magenta Book on evaluation. Offers detailed guidance on designing, conducting, and using evaluation to inform government policy and programmes.

- The UK Government’s Green Book on appraisal of policies, programmes and projects. Provides the methodology for economic appraisal and options analysis to ensure value for money in government projects and policies.

- Leading large scale change: a practical guide (leading large-scale change through complex health and social care environments). Practical NHS guide for leaders driving complex transformational change in health and care systems, with tools, case studies, and principles.

- Engineering better care: a systems approach to health and care design and continuous improvement. Sets out a systems-engineering approach to improving healthcare design, delivery, safety, and continuous improvement.

- The Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) complex intervention research framework. Framework for developing, evaluating, and implementing complex interventions in health research.