Kuberska, K. and Martin, G. (2025), What Is an Identifier Good for? Issues in Using Visual Identifiers to Improve Care for People With Dementia in Hospital. J Adv Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.17039

What is an identifier good for? Why they don’t always improve hospital care for people with dementia

Why it matters

As the UK population ages, the number of people experiencing age-related health conditions and neuro-degenerative illnesses such as dementia has risen.

As a result, many hospital patients have some form of cognitive impairment (where a person has trouble with mental abilities like memory, thinking, learning, or decision-making). In 2022/23, 44% of inpatients in English hospitals were aged over 65, and 10% were over 85. Caring for patients with cognitive impairment can be complex and as the number of people diagnosed with dementia in the UK increases, there is also an increasing need for resources to make sure that they receive high quality care.

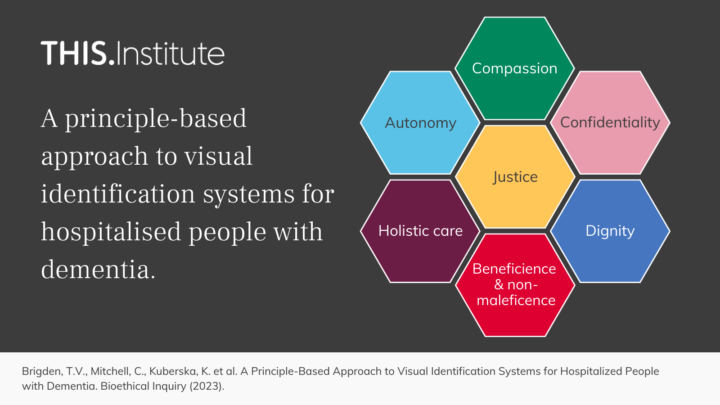

Many hospitals have introduced different strategies to help them better care for people with dementia, including the use of visual identifiers. These are small objects like stickers or wristbands placed near or on a patient to remind healthcare staff to offer them person-centred care.

Although variations on these have been widely used for over 20 years in UK hospitals, research shows that they do not always lead to better care, with studies highlighting several problems, flaws, and unintended consequences. Sometimes, identifiers can lead to care that is routinised and task-driven rather than person-centred.

Different types of identifiers carry different risks and benefits, and many hospitals use more than one kind, which may generate further issues and add to staff’s workload. We looked at how these systems work, how they differ from similar tools, and their limitations. We also considered the complex needs of people with dementia during hospital stays and questioned whether simple tools like visual identifiers can truly address these challenges.

What we found

Comparing visual identifiers for people with dementia with other common types of identifier can help us to better understand the problems they face.

Some of the distinctive features that identifier systems use to improve dementia care may be especially important. But the high expectations placed on them can also lead to them failing at least some patients.

A combination of the negative impacts of disclosing a patient’s dementia diagnosis, the unclear messages these identifiers often send, and the difficulty of knowing how to respond well means that they can become at best a blunt tool for achieving person-centred care. At worst, they can lead to harm by reducing a person to their diagnosis.

Identifiers can unintentionally lead to the ‘taskification’ of care – healthcare staff following a list of protocols rather than building a relationship with a patient through time, connection, and understanding.

In busy wards, the result might be that staff focus more on managing risks and following hospital routines – things that are easy to measure and audit – and not on embracing the need to develop relationships with every patient as an individual.

Other systems, like red wristbands to indicate a medication or other allergy, or colour-coded hats for newborns to indicate the level of support they need, seem to cause fewer issues because their message is clear and how people are expected to respond is straightforward.

We suggest that it is better to limit expectations about what visual identifiers can achieve for people with dementia in a typical busy hospital ward than to assume that they will necessarily result in high-quality person-centred care.

It is essential to ask who really benefits from these systems and what specific aspects of care they improve. Visual identifiers may have a useful role as a tool to help manage simple, vital, and sometimes even safety-critical, tasks. By being honest about their strengths and their limitations, we may be able to reduce the risk of visual identifiers inadvertently undermining person-centred care.